1.2 Assessment of Landscape Context

All forest restoration sites sit within wider landscapes of nature, forests, agricultural land, villages etc. What happens on the restoration sites influences its surroundings, nature and people, in multiple ways. It is important therefore to look beyond your site boundary when planning and implementing restoration. A landscape is a socio-ecological system, composed both of the biogeographical premises and human interactions in the past and the present, and is subject to internal (e.g., natural dynamics and succession) and external forces (e.g., climate change). Such a broader context should be evaluated from ecological, socio-cultural and socioeconomic viewpoints. In this way, projections on risks and opportunities for sustainable development can be assessed.

Landscapes come in all shapes and sizes, and what size is most important depends on the specific issue – such as the needs of certain animal or plant species, the kind of human activity taking place, or how the forest is being managed. Landscapes may have a single, a few, or several land cover types. Forest landscapes are dominated by forest land, but can also have other landcover types intermixed, such as water bodies and grasslands. The transition zones, i.e. the forest edges, typically contribute important ecological functions such as filtering, buffering, energy flow, and biodiversity.

Forest landscapes can form naturally or be shaped by human activity. Natural forest landscapes are often remote areas that have seen little or no human use, or they are small remaining patches of original forests. In contrast, human-shaped (or artificial) forest landscapes have been influenced by forestry or other types of land use. In Europe, most forest landscapes fall into this second category, with a long history of human impact. Ecological recovery into natural or semi-natural status occurs, however, on large-scale in, for example, the foothills forests of the Scandinavian Mountain Range – i.e. the Scandinavian Mountains Green Belt – but elsewhere in fragmented patches with old-growth and primary forests. As European forest landscapes contain a whole wide gradient of intensity of forest management, more intensively managed forests like age class forests with few tree species do not provide the same value to species preferring old-growth conditions. Thus, if such intensively managed forests sit next to remnant patches of high conservation forests, these intensively managed forests can still hinder ecological processes such as natural spread and migration of species in comparison to more natural forests.

Assessments of a forest landscape require a clear view of focal species, habitat or issue, i.e., to allow a definition and understanding of the context. Generically, however, assessments should include spatial distribution of core attributes, such as land-cover types, natural vs. artificial forests, high conservation value forests, successional states, native tree species, tree species mixture, presence of biodiversity attributes such as dead wood, vertical and horizontal heterogeneity, etc. Of specific relevance is the distribution of Annex 1 habitats (Annex I habitats are natural habitat types of community interest whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation. These habitats are listed in Annex I of the EU Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. More info here) other strictly protected areas, and areas that are subject to continuous cover forestry or other alternatives to industrial, rotation forestry. Ecological connectivity can be seen as an overall indicator that, if satisfactory, ensures natural spread and migration of species, as well as integrity of ecological functionality, also under climate change. More broadly, connectivity can be applied also to other key aspects of forest landscapes, such as connectedness for recreational purposes) and, as well as to intact transition zones from forests to water bodies (i.e., riparian forests) and land-cover types.

Related resources

Assessment of initial situtation of restoration areas

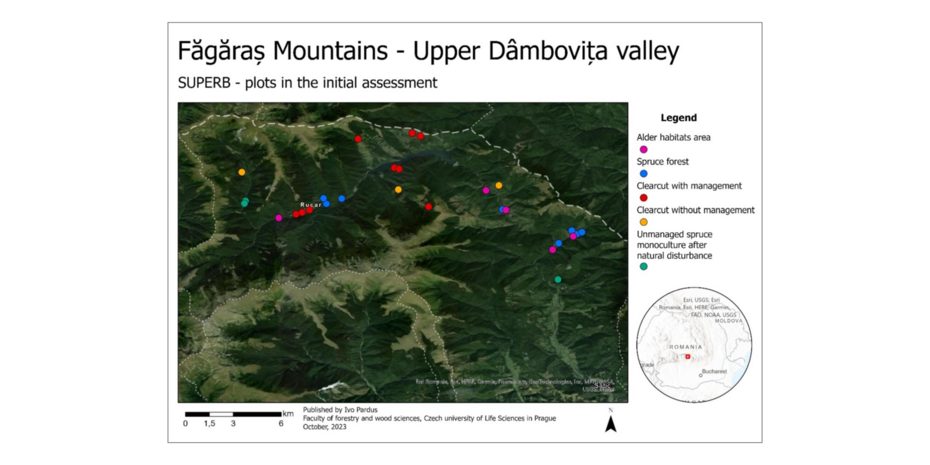

Assessment of initial situation is a monitoring protocol that describes setup design and methodology used to assess the current state of forest before applying any restoration measures.

Assessment of initial success and restoration efforts

Assessment of initial success and restoration efforts is a monitoring protocol that includes qualitative and quantitative assessment of early stages of restoration success (1-2 years after establishment) and efforts made to achieve a successful restoration.